Decentralising RAS Unit Processes to Lower CAPEX Part 3: Potential Applications in Shrimp Farming

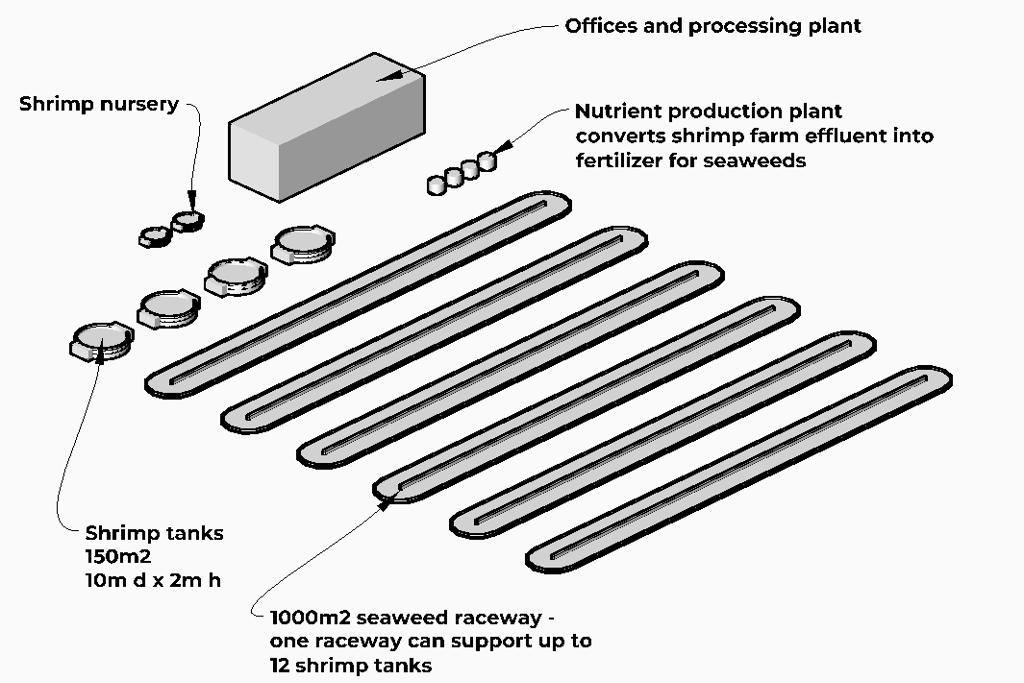

Could a shrimp farm be both highly productive and environmentally smart without massive investment? In this post, we explore self-contained hybrid RAS tanks that promise stable water quality and easier solids management. Discover how a modular design could turn shrimp effluent into a resource for seaweed cultivation.

Carlos

12/3/20254 min read

Introduction

In Part 2, I concluded by questioning whether it would be possible to double or triple stocking densities in decentralized RAS units. Recent work at ChimanaTech has shifted my attention towards shrimp farming, exploring how the self-contained hybrid RAS concept could be applied commercially.

Shrimp farming, particularly with whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei), is always evolving. Biofloc technology and recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) are increasingly used. In some cases, this leads to smaller production units that allow better control of water quality and pond hydrodynamics. However, this evolution also highlights a cost-performance tradeoff:

Biofloc systems are simple and cost less than RAS, but require complex management of live microbial communities. Floc overgrowth can lead to sludge sedimentation, productiong of nitrite, H2S, as well as incresased oxygen demand. Recirculating systems provide more stable water quality, but cost several times more.

The hybrid concept from this series aims seem then, well-fitting for this case. By integrating biofilters into the tank walls, the microbial community is stabilized, and airlift circulation provides oxygen solids transports to the center of the tank / pond. As shrimp are stocked a lower densities, airlifts should maintain adequate oxygen during most -if not all- of the production cycle.

Solids as the water exchange control parameter

Even with ammonia controlled via biofilters, solids accumulation remains a central challenge. Side-wall airlift-biofilter units create circular water movement, which helps concentrate solids in the center of the tank. Advanced outlets such as large conical drains, sometimes called "shrimp toilets," can trap solids efficiently.

Operating as a zero-exchange system is limited by nitrate accumulation, for which the safe upper limit is not well established, and by oxygen consumption from bacteria. Over time, bacterial growth may exceed what the airlifts can provide. When solids accumulation becomes significant, the system may require flushing or partial water exchanges to avoid high oxygen demand and excessive bacterial buildup. This approach positions hybrid RAS as a middle ground between biofloc and full recirculation systems.

Design Example: A 150 m³ Shrimp Tank

Tank Dimensions

The example tank has a volume of about 150 m³, with a diameter of 10 meters and a depth of approximately 2 meters. The diameter-to-depth ratio of 5 to 1 is favorable for solids flushing. A depth of 2 meters also provides thermal buffering between day and night temperatures.

Stocking Density and Feed Load

Assuming a maximum stocking density of 10 kg/m³ and a production cycle of three months with juveniles supplied externally, the tank can produce approximately 6 tons of shrimp per year if harvested four times annually. At maximum biomass, feeding would reach around 60 kg per day.

Biofilter Requirements

Biofilter requirements depend on feed load and ammonia production. For this scenario, the tank would require 15 to 20 m³ of biomedia. If the biofilters are as deep as the tank and filled to 50 percent, each biofilter unit would occupy roughly 10 percent of the tank area, split across two side-wall units. This provides sufficient surface area for nitrifying bacteria to stabilize ammonia.

Water Circulation and Oxygenation

Water circulation is driven by airlifts. The required circulation rate is based on the single-pass efficiency of the airlifts for oxygen transfer and nitrification. Assuming an airlift with known oxygen transfer efficiency of 80% the required turnover rate in the tank is about 5 times per hour, when the minimum DO admissible is 4mg, the maximum achievable is going into the tanks is 6.4 mg/l. The main strategy to reduce these high turnovers - and thus high rotational velocity - is to flush solids to reduce bacterial activity, turning the tank into a hybrid RAS at maximum loading. Additionally, playing with inlet geometry and orientation, adding obstacles in the tank such as substrates and environmental enrichment devices, or adding pure oxygen (expensive) can also help in reducing vorticity.

Additional Infrastructure

Infrastructure for the tank includes blowers for the airlifts, lightweight shade structures or bird netting, and pumps to provide water exchanges of approximately 90 m³ per hour. Effluent treatment devices are also necessary, including solids separators or settlers, anaerobic digesters to stabilize sludge, and fine solids control devices such as bead filters or sand filters.

Circular Economy Integration with Seaweed

The system can be integrated with marine aquaponics by using effluent water from shrimp tanks to fertilize ulva seaweed in raceways. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus are captured, enabling a low-exchange, near-closed system.

To be economically viable, the seaweed raceway system may need to be significantly larger than the shrimp farm. This creates excess filtration capacity for the shrimp effluents, which is good for the natural environment often surrounding shrimp farms. At pilot scales, a raceway of 1,000 m² (10 meters wide by 100 meters long) can handle effluents from 8 to 12 tanks, supporting shrimp production exceeding more than 40 tons per year while generating a seaweed crop.

This idea of a very large "green" component connected to a smaller fish farm is similar to the Superior Fresh aquaponic model in the United States, where a large greenhouse is connected to an Atlantic salmon farm. The greenhouse is sized to capture all effluents from the salmon farm, demonstrating how integrated aquaculture-agriculture systems can operate at scale with minimal nutrient discharge.

Conclusion

The self-contained hybrid RAS concept can be scaled up from a lab-scale system to a comnmercial shrimp farming one. It avoids full-scale RAS costs, allows environmental integration with seaweed production, keeps both CAPEX and operational complexity low, more in line with industry practice in the tropics.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to SeaweedLand for inspiring this exploration into sustainable seaweed integration with aquaculture effluents.

ChimanaTech

Chimana Management BV

Hemelrijk 2A

5281PS

Boxtel

The Netherlands

carlos@chimana.tech

+31 612 769 754

© 2025. All rights reserved.